A story of frozen speed, submitted by a person with an intriguing freezer experience.

Amy Reiswig is a researcher, writer and editor who abandoned her freezing home town of Montreal for temperate coastal life in Esquimalt, British Columbia.

Freeze.

As a verb or imperative, “freeze” ultimately means that something (or someone) gets slowed down, stopped. Frozen in time.

My Esquimalt, BC, freezer recently played host to a most unexpected guest: the icon of hyper movement, the hummingbird. An Anna’s Hummingbird, to be precise–Calypte anna. I found it freshly dead on the road after my lunchtime park walk. I couldn’t just leave it: it was quite literally a jewel from the sky. Still soft and limp, its fishing-line tongue protruding from needle beak. I carried it to work where I put it in the fridge (the neglected office freezer being frozen shut), until I could bring it home.

“And….do what with it?” my co-worker asked. I wasn’t sure. But I knew of a way to safely preserve it until I figured that out.

I wrapped the tiny green bird in paper towel and put it in a destined-for-recycling snack package. Like a bird mortician, I put it this little plastic casket in my freezer. Right between the vodka and last year’s uncleaned paint rollers wrapped in bags. What came to mind was a quote that used to hang above the door of my father’s marine biology lab at McGill University. I can’t remember it exactly now (and neither can my father), but it said something like ‘the fatal fascination of the beauties never comes to an end.’

*Bing!*

I knew why I was keeping the hummingbird in the freezer.

My father now lives in Victoria and is “retired,” but his fascination with the beauties of minute marine biology has never faded. Nor has his combination of workaholism and commitment to science. Therefore, he has a lab in the laundry room, boxes of specimens in jars in the garage and, what I wanted, a good microscope in his basement office.

My father’s microscope is normally used for examining the spicules of glass sponges, in order to make species identifications. Visual evidence is crucial to his work, and he has a specialty digital camera mounted on the scope with which he can take pictures. An interesting job, spent seeing things too small for other people’s eyes.

The hummingbird unfroze well: no freezer burn or lingering crispness. It was as pliable and soft as when I found it weeks before.

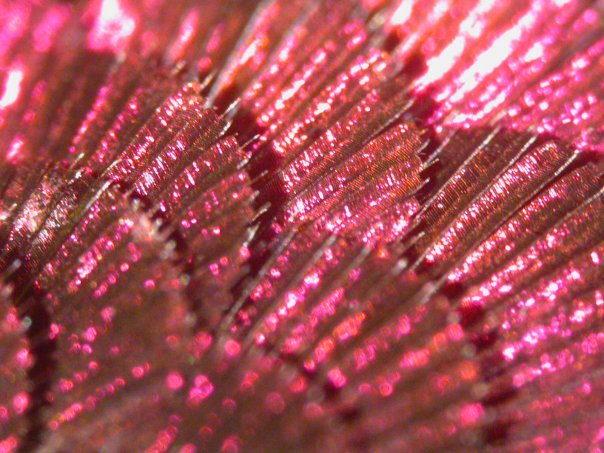

Under the microscope, the bird seemed botanical: feathers became palm fronds, ferns, leaves. They were wide and ridged and even clawed at the tip. I could see all the tiny zippers holding each filament of each feather together. Each tiny feather. I was in an Alice world of wonder. I very literally lost track of time down there. It reminded me of when I visited Sainte Chapelle in Paris, and the light through its 15-meter-high stained glass walls made me feel like I was inside the concept of magic.

My father was working on his computer behind me, but hovered. He handed me some tiny, thin pincers and pokers, since my now-huge-seeming fingers were much too clumsy to manipulate the bird or attempt to separate individual feathers.

I wondered whether I was intruding on his workspace, but every time I’d exclaim, “Holy crow, this is amazing!!” or some other effusion, I’d look over and he was always smiling. I think he finds my gushing enthusiasm both funny and refreshing. When he came over for a look at the hummingbird’s chest landscape, he also exclaimed, “Cool!” It was my turn to bring him a new scientific sight. There are many things about my father I don’t understand, but this passion for learning and seeing is one of the greatest gifts he has passed on to me, and is one of the ways we connect that I treasure. Another piece of magic.

While my education is in the arts, I’d have to say I’m a science amateur in the sense that I love being exposed to mysteries: of animals I’d never seen or heard of before, of things too small or too big to normally explore, of the world right in front of me. And, on reflection, it seems that’s what the various arts are about in their different ways, too.

Eventually, after taking a number of photos, trying to get the microscope to capture the hummingbird’s secretive electric shine, I laid it to rest in my parents’ backyard.

But none of this would have been possible without a very special and humble helper.

So: thank you. For giving me the time to think and make a plan. For making sure I didn’t have to pass on this bizarre and beautiful little chance. For allowing me to introduce friends and strangers to the hummingbird’s normally invisible details through microscope photography. For giving me a lovely afternoon with my father. It couldn’t have happened without you.

Thank you, sweet freezer.